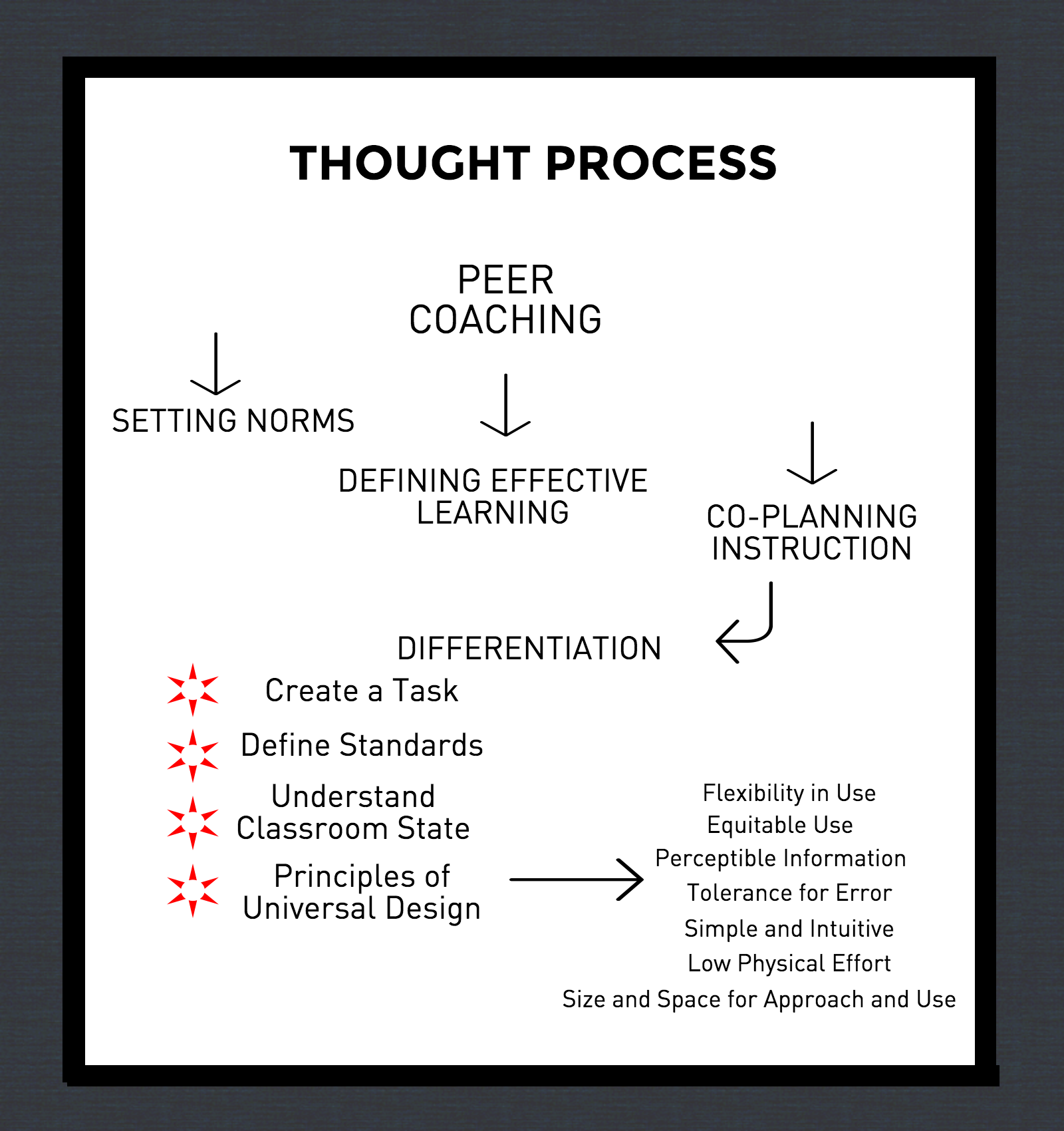

As part of my recent exploration of peer coaching, I have recently explored what it means to peer coach and what 21st century learning looks like in the classroom. Now, my attention has progressed to think about lesson improvement within the peer coaching process. As previously discussed, effective learning challenges students to shift from simple consumers of information, to producers of knowledge in the real-world (Foltos, 2013). For many, this type of learning is not easily integrated into daily teaching (Foltos, 2013). What steps are necessary to co-plan an effective lesson plan?

Creating a Task

Foltos (2013) wrote that first you need to create a task that is complex and real-world. It shouldn’t be too simple or too easily solved (Foltos, 2013). While this concept sounds good, it can be difficult to translate into a learning activity that is both relatable and digestible for students. Foltos (2013) suggested that real-world problems presented are aligned with student interest and that requirements can be easily defined and understood by students.

Defining Standards

Next, it is important to define the standards being focused on. There can be multiple categories of standards to consider: curriculum standards like those found in the Common Core, 21st century standards such as those with the Partnership for 21st Century Learning, and technology standards like the ISTE Student Standards.

Crafting Student Directions & Assessments

From here, the learning context can be defined. This might be more easily understood as a “series of carefully sequenced learning activities” (Foltos, 2013, p. 125). It is, of course, important to determine how the learning activities correlate with the standards (Foltos, 2013). Finally, student directions can be crafted, assessments can be created, and resources can be identified, all through a process of receiving and sharing feedback.

Differentiation

One of my collaborating partner’s current focuses is differentiation. As such, I thought it relevant to align this week’s guiding questions about co-planning lessons to questions of differentiation. Differentiation is easily discussed but not as readily implemented into the classroom. It remains a great theoretical concept that is difficult to implement on a daily basis, given time constraints and curricular demands.

What protocols can be used to collaboratively design differentiated instruction effectively?

The Importance of Peer Coaching

Latz et al. (2008) reaffirmed that one way to become better at planning with differentiation is to engage in peer coaching. Their study, “Peer coaching to improve classroom differentiation: Perspectives from Project CLUE,” sought to determine if engaging in peer coaching relationships had an affect on the ability to differentiate instruction effectively (Latz et al., 2008). The result was that it is an important aspect of implementing differentiation, specifically because it is collaborative, not evaluative (Latz et al, 2008). Foltos (2013) echoed this sentiment by writing that peer coaching’s focus on feedback, allows collaborators to improve student learning.

What is it?

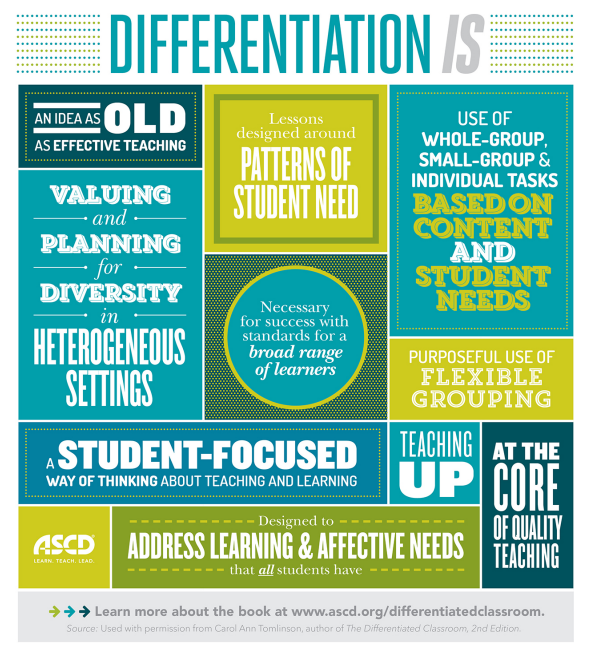

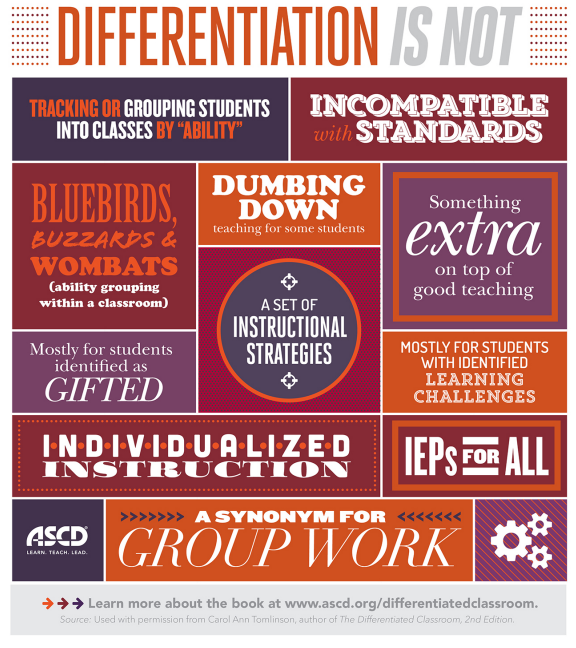

Our students face many different daily challenges. Varied reading levels, learning disabilities, and background knowledge are some of the many obstacles students work through (Meo, 2008). Meo (2008) assessed that the expectation and desire to meet the needs of all of these individual students is daunting and, sometimes, not entirely possible. It is often assumed that the teacher’s role in practicing differentiation is to both adapt current curriculum and to also add to it to meet the individual needs of students (Meo, 2008). She asserted that “Educators do not seem to question whether the burden of adaptation should fall on the curriculum itself—that the curriculum, and not the students labeled “special,” is what needs fixing” (Meo, 2008, p. 21). We might want to consider the fact that intrinsic issues with the curriculum design itself may be to inhibiting differentiation. Alternatively, curriculum designed for diverse learning opportunities creates opportunities for it (Meo, 2008). As part of the 2nd edition of her book, The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, Tomlinson (2015) created a helpful infographic to depict what differentiation IS and IS NOT below.

Universal Design

Meo (2008) looked at how the universal design for learning framework can allow all students from all levels and backgrounds to succeed, as opposed to targeting only certain students for additive or adaptive support. She continued that placing students in categories based upon accommodation needs (general education, IEP, 504, ELL, etc.) can inaccurately and unfairly depict the wider diversity of student learners in a classroom (Meo, 2008). As a result, if curriculum is designed to foster access for all learners, all students can benefit (Meo, 2008).

So, what is universal design? The term didn’t get its start in education in fact. King-Sears (2009) explained that the term was coined to define non-discriminatory architectural and product design. As a result of these design principles, buildings and homes would not require adaptations or adjustments for those with special needs. Rather, the building would be originally designed to function for all, often including ramps or wide doorways (King-Sears, 2008). King-Sears (2008) related this to education by stating that when instruction is designed for all students, special accommodations required for certain targeted students can simply occur more organically.

What does this look like? There are seven principles of universal design originally crafted for building and product design (Connell et al., 1997).

King-Sears (2008) identified how these universal design principles align with education.

Flexibility in use…

is achieved through learning activities that allow for a spectrum of interest and ability.

Equitable use…

recognizes pedagogical practice allows all students to access the learning.

Perceptible information…

means that curriculum in presented in a variety of methods and styles.

Tolerance for error…

is the practice of guiding students to make multiple attempts in their learning while providing feedback along the way.

Simple and intuitive…

instruction recognizes content delivery that isn’t confusing or lacking audience consideration.

Low physical effort…

means that materials of all kinds are easy to use.

Size and Space for approach and use…

recognizes that content is accessible and visual to all those in room no matter where they are seated.

While rooted in a different field, these universal principles provide a system in which access and flexibility benefits everyone on a spectrum, not only specific individuals (Meo, 2008). Before implementing these principles, it is important to set goals by identifying what one wants students to learn and keeping this consistent to ensure that high quality instruction is available to all learners (Meo, 2008). Then, it is important to understand the current state of one’s classroom, and recognize that the entire classroom has diverse needs (Meo, 2008). While this might be a shift in thinking, it prevents too much of a focus on only specific student needs. What barriers might exist in the classroom? What background knowledge are students arriving with? Finally, the principles of universal design can be considered and implemented. It is important to remember that there is never one way to teach all students effectively (Meo, 2008). So, what is the solution? According to Meo (2008) it is helpful in any differentiated classroom to “provide multiple representations and multiple formats for learning new ideas and concepts” (Meo, 2008, p. 26). The more student choice that is offered in activities, in assessments, and in the opportunity to learn and demonstrate understanding, the better (Meo, 2008). Finally, part of increased student choice is increased student involvement. Latz et al. (2008) argued that student involvement is one of the most important aspects of differentiated instruction. Active, rather than passive, learners are better able to learn at higher levels, no matter the starting point (Latz et al, 2008).

Resources

Connell. B. R., Jones. M., Mace, R., Mueller,J., Mullick, A., Ostroff, E., Sanford, J., Steinfeld, E., Story, M., & Vanderheiden, G. (1997). Principles of universal design. Raleigh: North Carolina Stale University, Center for Universal Design. Retrieved November 18, 2015, from https://www.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_ud/udprinciplestext.htm

Foltos, L. (2013). Peer Coaching: Unlocking the Power of Collaboration. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

King-Sears, M. (2009). Universal Design for Learning: Technology and Pedagogy. Learning Disability Quarterly, 32(4), 199-201.

Latz, A. O., Speirs Neumeister, K. L., Adams, C. M., & Pierce, R. L. (2008). Peer coaching to improve classroom differentiation: Perspectives from Project CLUE. Roeper Review, 31(1), 27-39.

Meo, G. (2008). Curriculum Planning for All Learners: Applying Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to a High School Reading Comprehension Program. Preventing School Failure, 52(2), 21-30. Retrieved from

Thanks for your thoughtful well-researched post on universal design! I appreciated the focus on student choice and involvement in the process. Enabling them to join in on making decision on their learning has lifelong impact.

Great find on Tomlinson’s infographics of what is and is not differentiation in the classroom. This is a challenging part of teaching especially for new teachers- How do we meet the needs of ALL students? The universal design framework seems to address this challenge. As you mentioned, both Meo and Latz agreed that the most important aspect of differentiation is providing students with choice and that they are actively involved with their learning. This is an area that continues to challenge me, especially the assessment piece. Giulia Forsythe’s “Universal Design for Learning” was a wonderful visual for understanding the principles, thanks for sharing. Great job, Annie!

Wow, Annie! As you know, much of the focus of my peer coaching relationship is on differentiation and this was so helpful for me to read. Tomlinson’s graphics were a true wake-up call, I have to admit that I see (and probably perpetuate) some of her “Is Not’s.” I was struck by the following passage, it was helpful for me to envision how differentiation could look and be successful: Meo (2008) looked at how the universal design for learning framework can allow all students from all levels and backgrounds to succeed, as opposed to targeting only certain students for additive or adaptive support. Thanks for a great post!