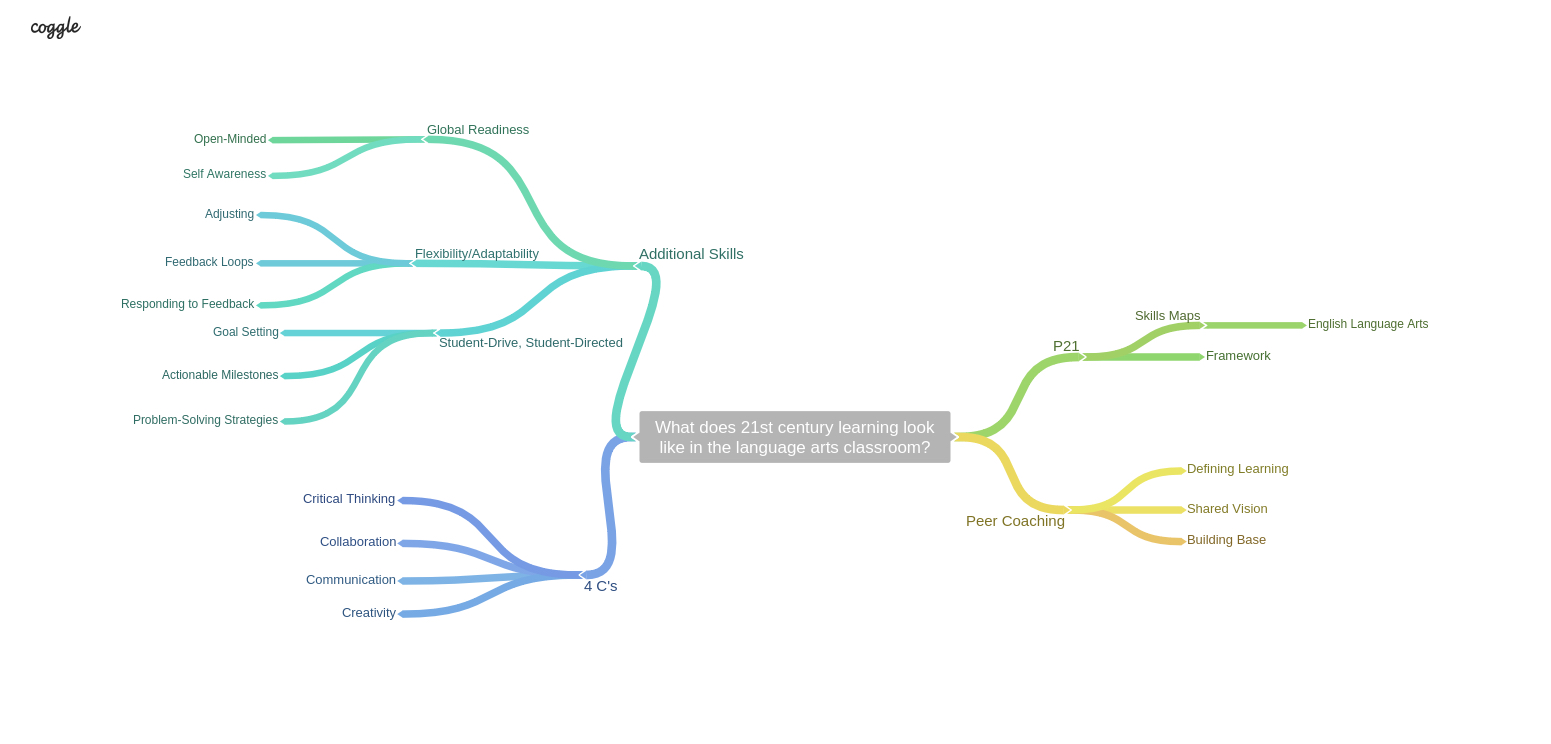

This week in my studies with the Digital Education Leadership program at Seattle Pacific University, I am continuing to explore ISTE Coaching Standards 1 and 2 by investigating what effective student learning looks like. Just as norms are an important part of a peer coaching relationship, so too is a shared vision for what effective 21st century learning looks like. This shared vision creates a starting place for any collaborative work.

The future of education is changing to respond to the internet’s information age. With an overwhelming amount of information accessible online, the role of teachers is less about possessing knowledge and more about facilitating learning driven by the students themselves. It is about preparing students for the emerging skills of tomorrow’s jobs. Resources like the Partnership for 21st Century Learning and the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) set out to define what effective students learning looks like to get there. Commonly referred to as the four C’s, communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity are referenced as the basic elements of 21st century learning. However, these skills can appear vague or nebulous compared to the daily needs of instruction. As a result, it is important for coaching teams to define which skills are most important to student success (Foltos, 2013). The work to define these characteristics becomes “a road map that describes what teachers need to do to improve their practice and specifics on how to shape teaching and learning activities to reach their goals” (Foltos, 2013, p. 105). Foltos (2013) provided a solid reminder that while it is easy to say that students need to learn 21st century skills, it is more challenging to transfer skills such as critical thinking to daily classroom practice.

How do we turn these frameworks, standards, visions and characteristics into realities? What does it looks like, specifically in an English language arts classroom?

How Teachers are Prepared to Implement Effective Learning

According to Perkins (2010), the first step might be to address the manner in which teachers are prepared to implement effective learning. Instructional shifts place lofty demands on teachers, and support in the form of professional development is crucial to build the capacity necessary to achieve this shift (Perkins, 2010). While it is common to ask teachers to attend professional development sessions, workshops or conferences, daily professional development is an important part of transforming teaching; peer coaching is one such daily professional development model (Perkins, 2010). Perkins stated that illustrating 21st century learning can start with the establishment of a personal learning network. A personal learning network provides teachers access to personalized points of information and support that empowers the teacher in their specific curriculum and begins to self-direct instructional transformations (Perkins, 2010).

What 21st Century Learning Looks Like

Kivunja (2014) works to unpack the Partnership for 21st Century Learning organization’s framework, among other resources. While the four c’s are certainly integral to future readiness, Kivunja focuses on three skills that are less often highlighted.

Flexibility and Adaptability

Jobs are emerging and shifting rapidly, which means that not only do few employees stay in the same jobs for thirty years, roles within certain fields shift regularly. Employers desire employees who are capable and enterprising in the face of change (Kivunja, 2014). Much like the finches studied by Charles Darwin on the Galapagos Islands, students need to be able to adapt to prosper in their environments.

- “Galapagos finches studied by Darwin,” Charley Harper Contributed by V. Boehm to SU Professional and Technical Writing is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

What does flexibility and adaptability look like in the classroom?

Kivunja (2014) stated that students should be able to adjust to change with ease and without emotional compromise. Therefore, they should be able to respond to positive or negative feedback, originating from various sources. and adjust as needed (Kivunja, 2014). Teachers can purposeful implement strategies for responding to feedback in the language arts classroom to flex this adaptability muscle (Kivunja, 2014). Engaging in regular feedback may require a focus on constructive comments over grades, and feedback might come in the form of probing questions that prompt further thinking (Kivunja, 2014). While it is a shift to ask students to feel satisfied with open-ended growth instead of summative grades, these approaches increasingly involve students in their own learning (Kivunja, 2014).

Student-Driven, Student-Directed Learning

Kivunja’s (2014) also worked to illustrate student-driven and student-directed learning. We may have become increasingly accustomed to these terms, but how do we teach students to take ownership in and have enthusiasm for their learning? Kivunja (2014) suggested teaching students to set goals independently, as well as manage their own time and ongoing tasks as part of larger projects. We want our students to be self-starting employees, who independently propose opportunities for work, rather than employees who stand by, waiting to be told what to do next by their supervisor (Kivunja, 2014).

What does student-drive, student-directed learning look like in the classroom?

This can start in the classroom by teaching students to create SMART goals, to plan for long-term projects involving actionable milestones, and to problem solve using strategies when technological issues or unfruitful research results prevent momentum. My colleague, Marsha Scott, astutely noted that we often ask students to create goals, only to never return to them. Our role as a teacher in the student goal setting process is important. Consistent feedback and the revisiting of goals set can be challenging to find time for, but is an important aspect of fostering project management skills.

Global Readiness

Finally, Kivunja (2014) identified the word global as integral to this conversation by defining how students’ ability to communicate and collaborate globally is an important aspect of the 21st century. As we know, technology has brought humanity together on a grand scale making the ability to connect with others around the planet easy and instantaneous. Recently, upon initiating a global collaborative project in my own classroom, I tried to set the scene by asking students if either one of their parents ever work with people in other countries. In every class period, three quarters of the classroom raised their hands, which may be due in part to the widespread tech industry in our area, but it is not farfetched to assume this will continue to be increase.

What does global readiness look like in the classroom?

Kivunja (2014) wrote that students need to know “how to deal in such an international arena with an open mind that is receptive to different ideas and values” (p. 7). Additionally, students need to learn that the ideas and practices in which they are accustomed are not better than the ideas, practices and values of others (Kivunja, 2014). How do we practice this ? Well, it starts by providing opportunities to connect and communicate with students living in other cities, states, and countries around the world. Tools like Skype in the Classroom, Twitter, ePals, LumenEd, and simply blogging can provide forums for students to make connections and practice these skills.

Illustrating 21st Century Skills in the English Language Arts

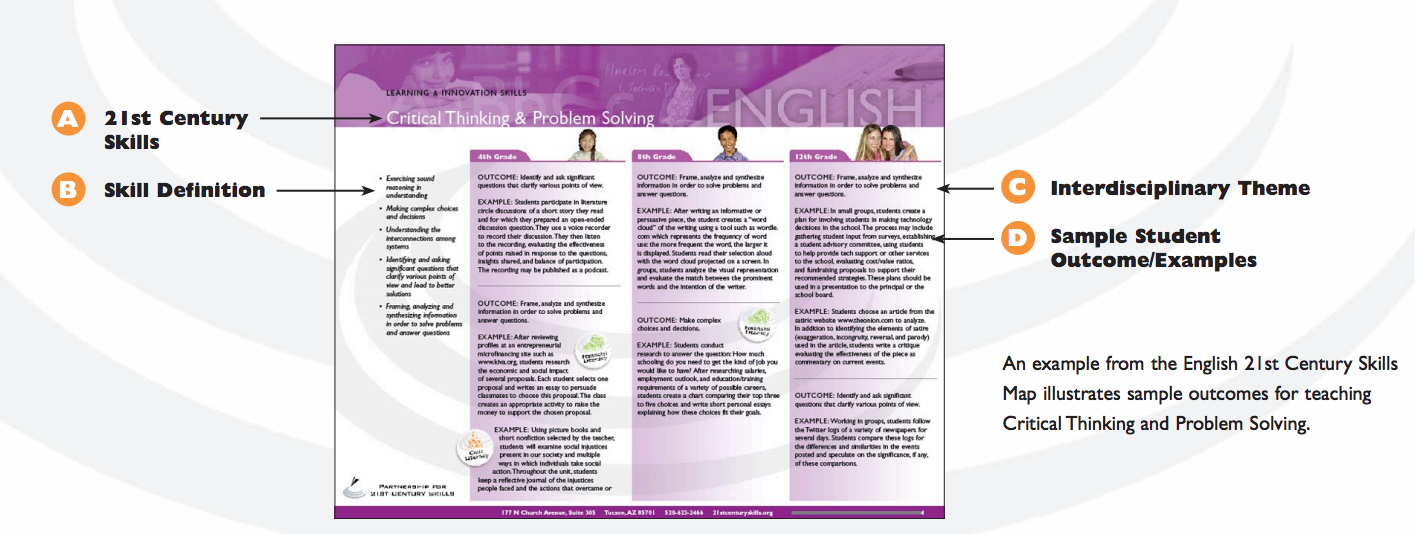

Since my triggering event question was specifically targeted to the language arts classroom, I actively sought out specific resources that might help identify exemplars in this content area. I returned to the Partnership for 21st Century Learning resource and found a set of skills maps focused on various content areas: Math, World Languages, Arts, Geography, Science, Social Studies, and English. These skills maps identify an outcome and an example of a learning activity in elementary, middle, and high school for all of the following 21st century skills.

- Creativity and Innovation

- Critical Thinking & Problem Solving

- Collaboration

- Information Literacy

- Media Literacy

- ICT Literacy

- Flexibility & Adaptability

- Initiative & Self-Direction

- Social & Cross-Cultural Skills

- Productivity & Accountability

- Leadership & Responsibility

Below is an example from the English Skills Map in the Social & Cross-Cultural Skills section:

As evidenced, they are not terribly specific, nor are there lessons plans attached. However, these exemplars are a great place to start a conversation about what effective 21st century learning looks like. One downside is that these documents can become quickly outdate, as specific digital tools are referenced that may no longer be relevant. Published from 2008 -2011, the digital tools referenced reflect this. Unfortunately, the 2008 English Skills Map is one of the oldest and it does feel, at times, out of date. However, I would still advocate that these resources are a solid place to begin defining models in a peer coaching relationship since the ideas remain grounded in skills.

Resources

Foltos, L. (2013). Peer Coaching: Unlocking the Power of Collaboration. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Kivunja, C. (2014). Teaching students to learn and to work well with 21st century skills: unpacking the career and life skills domain of the new learning paradigm. International Journal of Higher Education, 4(1), p1. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1060566.

Partnership for 21st Century Learning (2008). 21st Century Skills Map English. [PDF file]. Tucson, AZ. Retrieved from http://www.p21.org/storage/documents/21st_century_skills_english_map.pdf.

Perkins, J. (2010). Personalising teacher professional development: Strategies enabling effective learning for educators of 21st century students. Quick, (113), 15-19.

You made an excellent point at the very beginning of your post: a shared vision is needed to begin the collaboration work in a peer coaching relationship. I like how you focused on Kivunja’s three skills and then provided examples for implementing these skills in the area of language arts. These three skills, which I believe are important, also align well with the 4Cs and could easily be embedded within learning activities. Thanks for sharing your vision of using 21st century skills. Great job, Annie.

Great post, Annie. As much as I was intimidated by coaching initially, I’m really starting to see what a difference it can make. The following passage you wrote was so visual in helping me understand: “Commonly referred to as the four C’s, communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity are referenced as the basic elements of 21st century learning. However, these skills can appear vague or nebulous compared to the daily needs of instruction. As a result, it is important for coaching teams to define which skills are most important to student success (Foltos, 2013).” Those skills are vital and can be obtained through student-driven activities, yet if teachers are uncomfortable broaching these skills/subjects, the students will miss out. Workshops are generally one and done, we can help bring these skills into our schools through peer coaching. Great, great post!

I couldn’t but help to think about how this shift in education makes the time students spend in school much more like the time they will spend in a 21st century career path (maybe not all jobs though). You rightly point out the need to proactively engage our students in new ways so they take control of their own learning. This mirrors the future of managing their own work projects. To that end, you point out the work of Kivunja and in particular this:

“Kivunja (2014) suggested teaching students to set goals independently, as well as manage their own time and ongoing tasks as part of larger projects. We want our students to be self-starting employees, who independently propose opportunities for work, rather than employees who stand by, waiting to be told what to do next by their supervisor (Kivunja, 2014).”

This is so important! Great post, Annie and I hope it sparks conversation with our peers about how to transform the learning environment more!