As part of my studies with the Digital Education Leadership program at Seattle Pacific University, I recently engaged in and completed an exercise in peer coaching with a new teacher. I considered the additional challenges that face new teachers in the first few months of school and transitioned from an advocate to a collaborative partner, capable of leading and guiding inquiry. I practiced communication skills, including active listening and questioning strategies as my collaborating partner and I worked to build lessons together. Much of my work in this course centered around the study of Peer Coaching: Unlocking the Power of Communication by Les Foltos.

How can a school without a peer coaching program still benefit from the peer coaching method?

As part of my reflection, I am considering how I can continue to engage in peer coaching practices without a defined structure already at my school. While an official program would be beneficial, I have come to see that it is not critical. Perhaps the label of peer coach is not the most meaningful piece. Rather, the tools I’ve learned from studying peer coaching can really be transferred to any collaborative practice.

What is essential to support and sustain your success as a coach? What support do you need from your school to support success in your coaching work?

Research by Jewett and MacPhee (2012) suggested that collaboration and peer coaching is most successful when communities are focused on similar goals and are willing to share experiences. My colleague Marsha Scott was insightful to wonder why this is often such a difficult task. This would certainly be a place to focus my energies in future practice.

Foltos (2015) wrote that schools who only dip their toes into the peer coaching world don’t often see lasting impact. In order for coaching to be most successful, coaches and principals have to engage in an ongoing relationship, establishing plans that consider school or district initiatives and engage the willing (Foltos, 2015). How does this process begin? Often teachers don’t know how to approach colleagues about peer coaching, fearing that colleagues might find it “at best uncomfortable and at worse presumptuous” (Jewett & MacPhee, 2012, p. 106). While I have noticed that via my work, a few teachers have brought along inquiries or an interest in feedback, administrative support to identify interested parties for might be useful. Sharing out our experience to others could also open the door to others. Even without widespread implementation, the success of one partnership shared with the larger school community can engage both interested and disinterested parties (Foltos, 2015).

Another idea to establish a culture of peer coaching practices came from The Harvard Business Review. Ferazzi (2015) highlights that staff meetings can be used to practice collaborative strategies. Such a practice would shift the intention of meetings from information dissemination to a forum for collective problem solving (Ferazzi, 2015). This leaves everyone in the room positioned as a resource of expertise (Ferazzi, 2015).

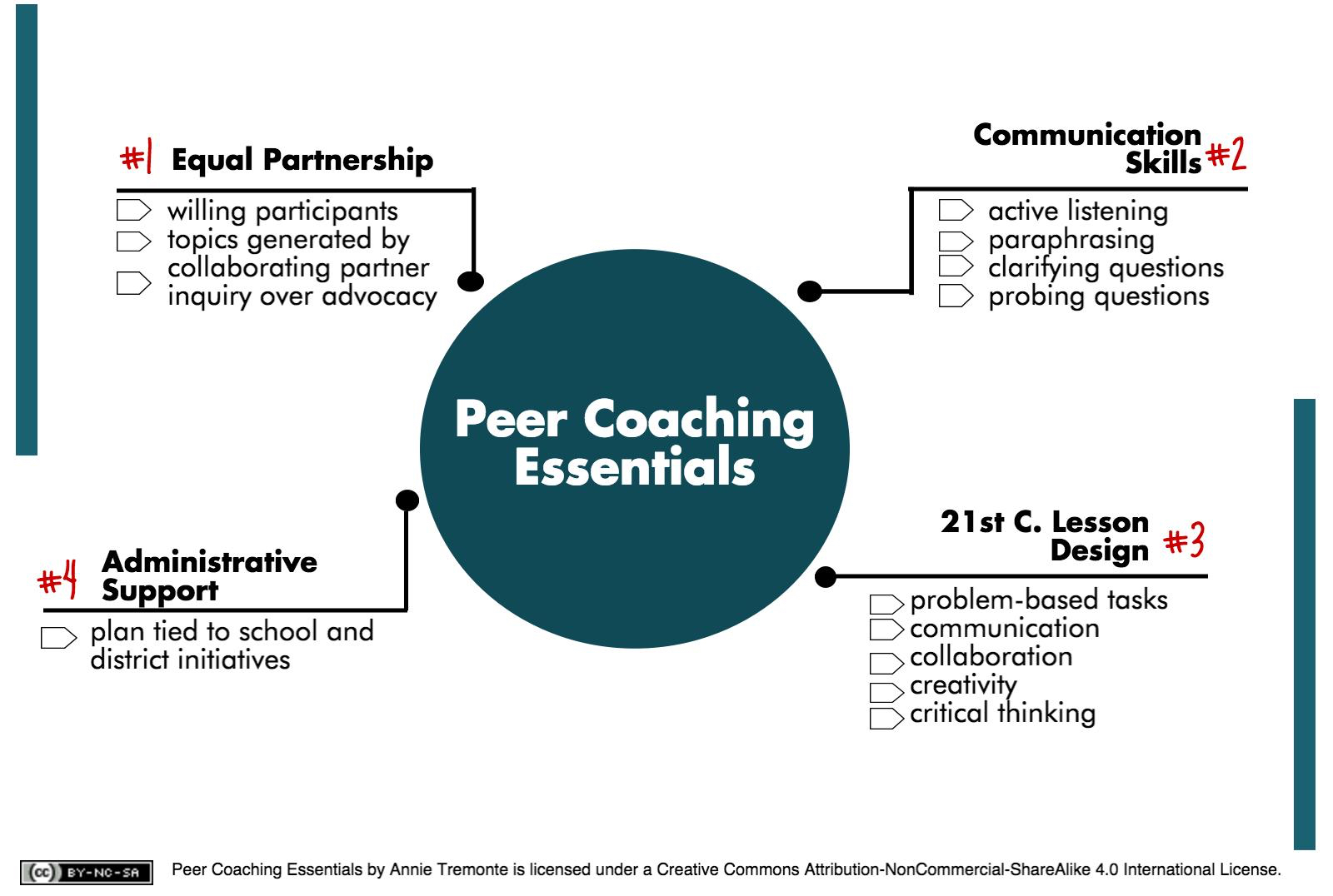

Once a coaching relationship is established, establishing equal partnerships is critical (Jewett & MacPhee, 2012). It is important that the needs and interests of the collaborating partner are at the forefront of the work. Otherwise, the practice can become inauthentic (Jewett & MacPhee, 2012). My current peer coaching relationship developed out of a mentorship with a new teacher. While our initial work primarily focused on daily needs, it has purposefully transitioned into a collaborative partnership centered on my collaborating partner’s needs and interests.

What worked well? What needs to change?

Together, my collaborating partner and I designed lessons that addressed differentiation within our secondary social studies curriculum, a topic of interest for her. We utilized online differentiation tools, like NewsELA, to teach current events driven by student interest and choice. We crafted lessons that utilized homogenous and heterogeneous groupings to jigsaw textbook content into mini-projects, designed for students to analyze and synthesize information into creative content. 21st century skills were addressed, essential questions were defined …and redefined, a focus on differentiation was maintained, and technology was organically implemented. We set SMART goals to address students’ ability to analyze evidence in support of claim and scaffolded lessons towards this goal. Of particular note was also our ability to move beyond “just in time” meetings. Finally, the collaboration left both of us with useful ideas for the future. If we were to follow-up on this lesson design, the goal would be to get even further along in the lesson design process, and to incorporate problem-based tasks, discuss assessment practices tied to standards, and craft student directions.

What do you see as your strengths and weaknesses as a coach?

One of my most significant personal goals was to develop communication skills, to include active listening, paraphrasing, clarifying questions, and probing questions (Foltos, 2013). I believe my participation in peer coaching was a successful exercise in raising my comfort level with these skills. I did a lot more active listening, restraining myself from advocacy in sharing past experiences and suggesting tools. My active listening and paraphrasing also created opportunities for recognition of my partner’s successes in the classroom. In the future, I would seek regular feedback from my collaborating partner as well by asking questions like, “Is this approach to collaboration working for you?”

What additional professional learning do you need to become a more effective coach?

While I feel that I have a baseline understanding of what being a peer coach looks like, seeking out additional online or face-to-face training could be beneficial. Engaging in professional learning communities, like those on Twitter can be a useful starting place. One example is the ISTE EdTechCoachesNetwork, or the hashtag #etcoaches to find engage in useful professional conversations.

Resources

Ferazzi, Keith (2015). Use your staff meeting for peer-to-peer coaching. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2015/02/use-your-staff-meeting-for-peer-to-peer-coaching

Foltos, L. (2013). Peer Coaching: Unlocking the Power of Collaboration. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Foltos, L. (2015). Principals boost coaching’s impact: school leaders’ support is critical to collaboration. Journal Of Staff Development, 36(1), 48-51,.

Jewett, P., & MacPhee, D. (2012). Adding collaborative peer coaching to our teaching identities. The Reading Teacher, 66(2), 105-110.

Annie, fantastic job! Your “Peer Coaching Essentials” chart displays a wonderful overview of skills learned this quarter. And I noticed that you combined your reflection questions which worked well with the responses. The section, “What worked well and What needs to change?” provides insight to a successful collaborative experience with your peer. Your co-partner is very fortunate to have you as a mentor teacher.

As you mentioned, your personal goals were to develop better communication skills such as active listening, paraphrasing, and clarifying questions. I personally know you have attained those goals as you have demonstrated these skills during our practice sessions. Great job and thank you for sharing your coaching experience!