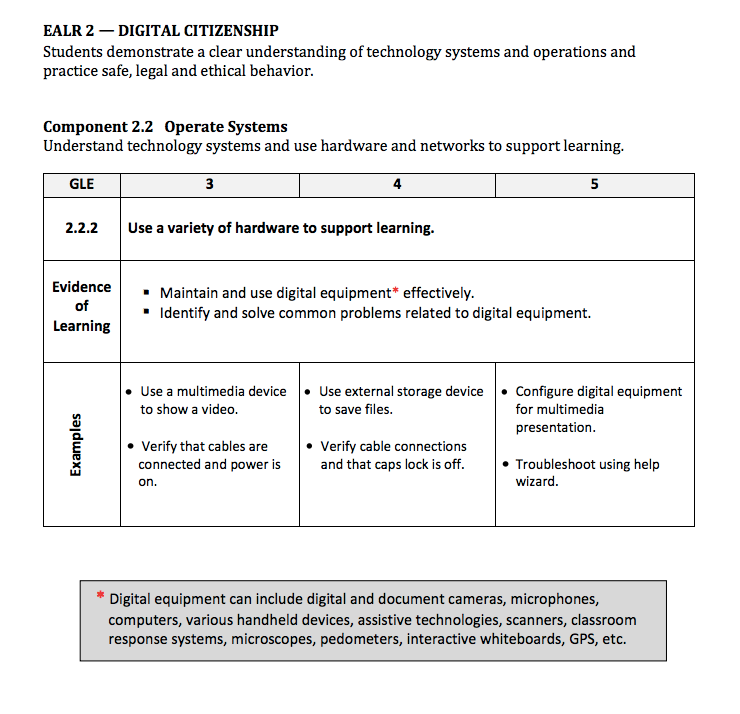

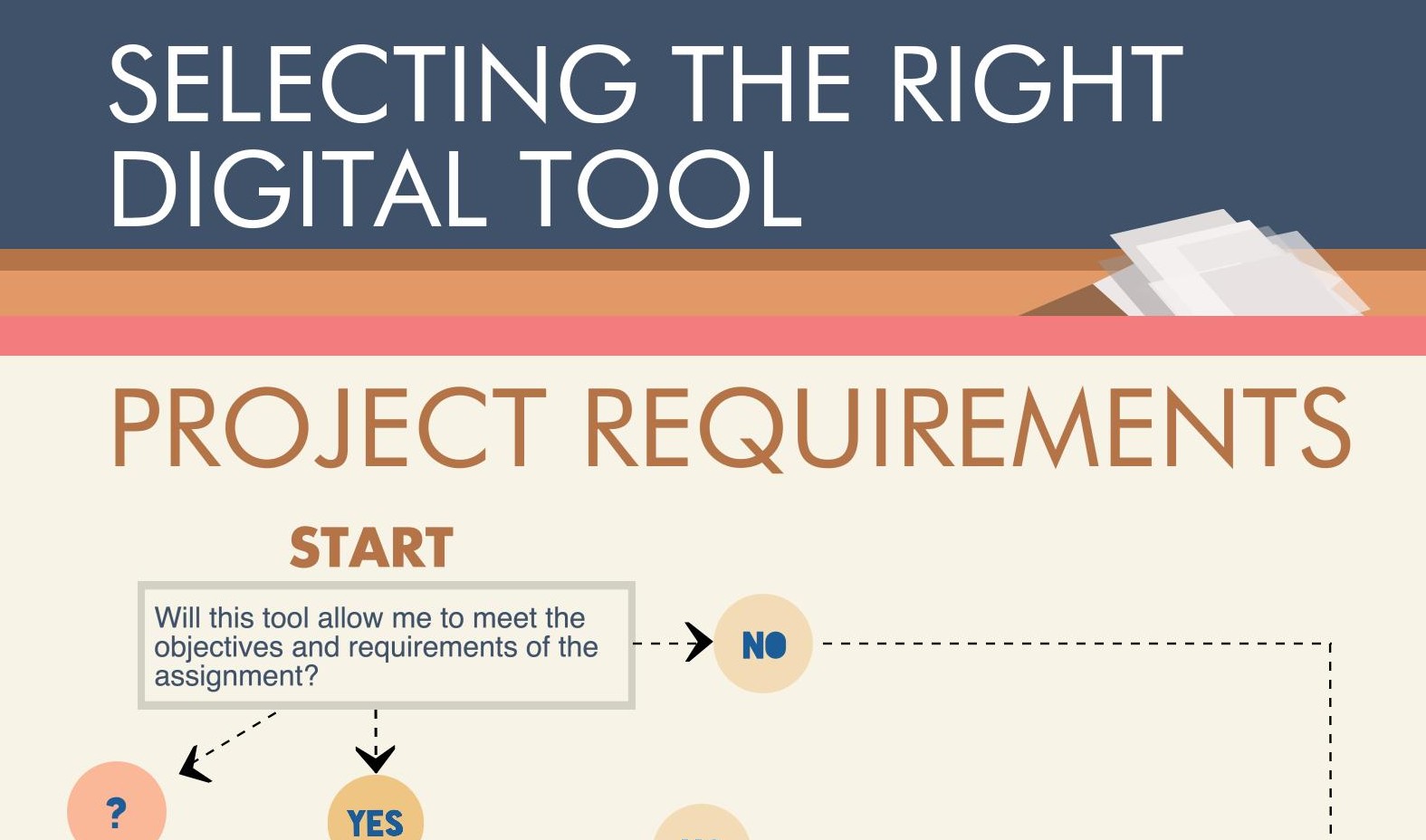

This week, as part of my exploration of ISTE Coaching Standard 3, I began to think about what an ideal digital learning environment might look like. My process began with my first post, Exploring my Ideal Digital Learning Environment. I started by reviewing three readings that explored the TPACK model, each one seeming to build on next ideologically in the integration of content, pedagogy, and technology. My takeaways from these readings were that content and pedagogy must work together to meet specified learning needs alongside the support of purposefully chosen technologies (Mishra & Koehler, 2003). I was also reminded that technology-supported learning is not reliant on the “what,” in this case the type of device, but rather “how” technology is used by the teacher to support objectives (Polin & Moe, 2015). Learning in this model should be student-centered and student-directed, and one method of encouraging student ownership of learning is to embrace a Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) program in the classroom.

Lai (2013) discussed the importance of teaching on a continuum of formality, in which learning is a daily practice that is not segmented between the informality of online interactions at home and the formality of teacher-directed use of technology at school. The interest-driven communication and collaboration by students on social media, on blogs, and in game play should be a catalyst for learning in school, while formal learning in school should also foster learning to continue beyond the school walls. While this is a device-agnostic sentiment, the relationship of personal devices to this continuum is undeniable as mobile devices travel with students between these settings. Additionally, Norris and Soloway (2011) outlined the prevalence of mobile devices on a global scale to outline the potential of taking advantage of such a widely-adopted technology.

Propelled by limited access to technology in my own classroom, I implemented a pilot BOYD program last year. I found the program to be valuable and successful, despite clear challenges. My emerging action plan for an ideal digital learning environment will revolve around the use of BYOD. I plan to consider how my past experience with BYOD, current research and received feedback assist my action plan for an adoption of this type of learning environment.