This week in my graduate studies, I looked at ISTE Teaching Standard 3 or “Model digital age work and learning.” The broad implications of this standard initially left me wondering where to start. The more I thought about it the more I realized that, in many ways, I have lived this standard over the past year. I investigated the following two indicators, with a focus on the audience of my peers.

- Demonstrate fluency in technology systems and the transfer of current knowledge to new technologies and situations

- Collaborate with

students,peers,parents, and community membersusing digital tools and resources to support student success and innovation

This school year has seen a major shift in my instruction. Due to the influence of my graduate studies, I have both experimented with and implemented more new ideas with technology, than ever before in my past seven years of teaching. While I have never felt behind in my use of technology, I have certainly never been ahead. Previously, digital tools have felt additive, as opposed to integrative. With new tools emerging all the time, I found myself overwhelmed. I viewed digital tools as finite tasks to master, instead of part of a larger pedagogical approach. As my own discovery of education technology has emerged and left my excited to share, I now wonder how I can become a leader in this field. What are the best methods for sharing my own shift in mindset and becoming a resource to fellow educators?

How can educators share and model successful and unsuccessful technology tools and ideas to colleagues in a manner that is useful, applicable, and trustworthy?

Collegiality

If I reflect on my lack of experimentation in past years, I am reminded that new ideas have been often shared with me in presentations at professional development settings. These have been static in nature, and rarely, ever collaborative. However, this year, that has changed. Learning and improving any practice doesn’t happen in isolation. While informal in nature, my collaboration with one particular colleague this year has resulted in impactful change for my students.

Studies by Patrick, Elliot, Hulme, and McPhee suggested that less formal aspects of professional development, in the form of collegial relationships that embody communication and reciprocation of ideas, are very powerful (2010). In “Normal of collegiality and experimentation: workplace conditions of school success,” Little studied the contributing factors of educator interactions and its effects on school success (1982). Her findings support that successful schools have educators who participate in “frequent, continuous, and increasingly concrete and precise talk about teaching practice,” who “plan, design, research, evaluate,and prepare teaching materials together, “ and who “teach each other the practice of teaching” (Little, 1982, p. 331). Additionally, reciprocity of collaboration among teachers is crucial despite different roles such as grade, content, or status (Little, 1982). Little concluded that the development of educators is most apparent when collegiality is both standard and widespread (1982).

An Inquiry Model with Support

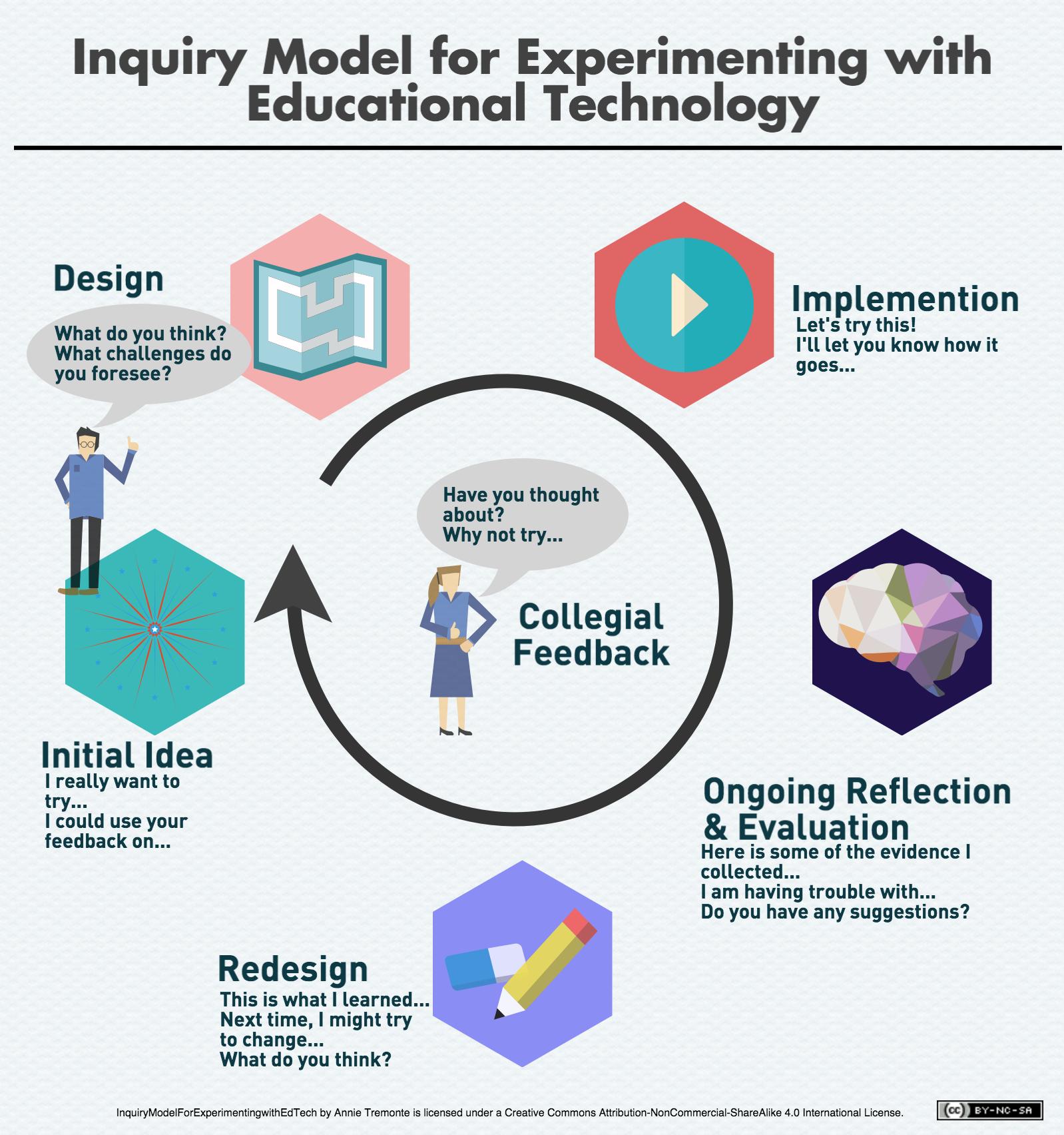

Successful advancement in instruction often begin with new insight. From here, an educator often experiments with how to implement the new lesson, activity, teaching method, or tool. Adjustments take place as the teacher witnesses unforeseen issues and formatively assesses student learning. Reflection pushes continuous adjustments into the future. However, teaching and learning does not occur in isolation. Each step of the instructional design process is best served with the collaboration of others, in the form of feedback along the way. This collaboration lends itself to safe experimentation and, trust is established. In my own experience, my colleague sees that despite my emerging excitement in and knowledge of digital tools, I need her expertise. We have a reciprocal system of support. To support this collegial feedback loop, the collection of evidence is important. For example, anecdotal records of how the class received and managed new information, formative assessment data to show levels of student understanding, and even student surveys are integral to the inquiry process, as well at to collegial discussions. I created the infographic above to depict the inquiry process for educator experimentation with new tools, with collegial feedback at the heart of the process.

In Practice

As I started off this school year with education technology on the brain, I often went to a particular colleague to ask questions. I was surprised to learn that despite teaching in a paperless classroom, she often feels unprepared to integrate technology. Rather, she admitted that her instruction has often mirrored previous models, just on the computer. We quickly realized that we both brought important perspectives to the table. She brought years of experience observing how students behave in a connected classroom, and I came to the table excited to offer up some news ideas. This collegial relationship has become a useful sounding board year for both of us to experiment. Together we have taught and refined the implement of student book trailers, infographic lessons, website building, blogging, and the use BYOD in the classroom. There are times when our attempts are unsuccessful, but our reflective discussions support the evolution of our ideas.

EdCamp

The growth of the EdCamp model of professional development speaks directly to the power of collegiality. While I have only attended one so far, it is apparent to me that this model of learning fits the informal and collegial mold, while also encouraging experimentation and reflection. Often referred to as an unconference, there is no prescribed agenda. Instead, personalized interests are shared in the morning, leading to the impromptu creation of sessions. Attendees and presenters are one in the same. In this sense, everyone is working together to make the day a success. Collaborative design leads to the professional development. Another key element is trust. Teachers are trusted as professionals who not only innovative, but are eager to continue to develop their craft in order for the EdCamp model to work (Swanson, 2014).

Professional Learning Communities

www.MarzanoEvaluation.com

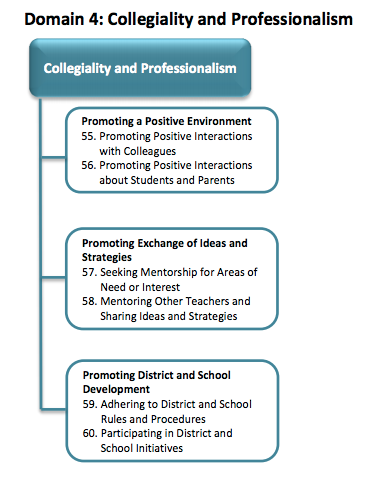

Some might suggest that the ideas outlined above mimic the expectations of a professional learning community, or PLC, as outlined by DuFour and adopted in many schools. However, as long ago as 2004, Dufour himself noted that the understanding of a PLC has morphed in recent years and may have lost some of its intended meaning. To many educators, professional learning communities connote mandatory meetings. Of course, by design, this is not the intent at all. DuFour writes that as educators we have to engage in a continuous conversation to determine what we want students to learn, how we will know that a student has achieved mastery, and what steps will be taken when learning has not been achieved (2004). A focus on teacher collaboration is crucial to this end goal. Marzano also included the importance of collegiality in a professional setting in domain 4 of his widely used teacher evaluation model by including the expectation that educators are ”promoting a positive environment” and “promoting exchange of ideas and strategies” (2013).

Communities of Practice

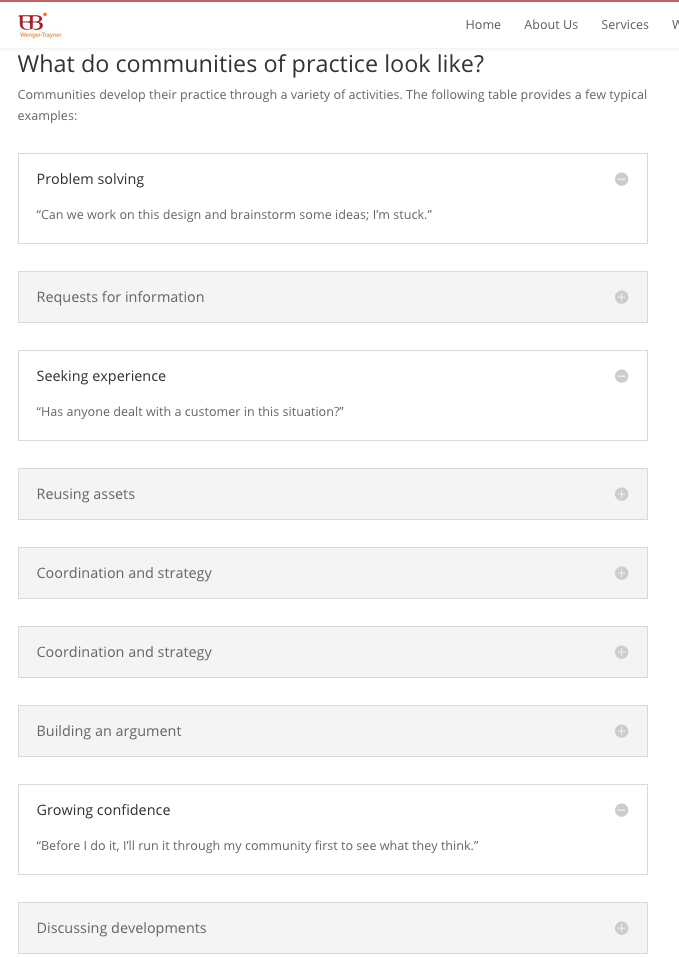

As I shared some of my thoughts to my graduate cohort,@ingersoll_ryan mentioned the term “communities of practice” to me. He regularly institutes this idea to engage in professional conversations at work and finds them to be very successful. Bates explained that the term reflects the daily and natural communities we are already in; these informal and self-directed communities are the forums in which we experiment, construct new meaning and connect with others (n.d.). @ingersoll_ryan suggested that meeting away from school or work can be a worthwhile change of environment that best supports the building of trust, informality and overall enjoyment. This is a valuable idea that is often overlooked. However, I would contend that even online spaces like Twitter are a change in environment that offer up an informality that supports collegiality, experimentation, and the construction of new ideas. Wenger and Trayner wrote extensively about communities of practice and outline three key factors: domain, community and practice (n.d.). The domain references to the shared activity, the community references the relationships, and the practice indicates the experience and effort put forth (Wenger-Trayner, E. & Wenger-Trayner, B, n.d.). On their website, they outlined some examples of questions one would see in a community of practice. These questions are actually very similar in scope to the ones I suggest in my inquiry model infographic above.

I am eager to learn what others think about this idea. Do you see value in collaborative methods as much as standard modes of professional development? What has been your experience?

Resources

Bates, T. (2014, October 1). The role of communities of practice in a digital age. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.tonybates.ca/2014/10/01/the-role-of-communities-of-practice-in-a-digital-age/

DuFour, R. (2004). What is a professional learning community? Education Leadership. 61(8), pp. 6-11. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/may04/vol61/num08/What-Is-a-Professional-Learning-Community%C2%A2.aspx

Little, J. (1982). Normal of collegiality and experimentation: workplace conditions of school success. American Educational Research Journal. 19(3), pp. 325-340.

Marzano, R. (2013). The Marzano Teacher Evaluation Model. Retrieved from http://tpep-wa.org/wp-content/uploads/Marzano_Teacher_Evaluation_Model.pdf

Patrick, F., Elliot, D., Hulme, M., & McPhee, A. (2010). The importance of collegiality and reciprocal learning in the professional development of beginning teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 36, 277–289.

Swanson, K. (2014). Edcamp: teachers take back professional development. Education Leadership. 71(8), pp. 36-40. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/may14/vol71/num08/Edcamp@-Teachers-Take-Back-Professional-Development.aspx

Wenger-Trayner & E. & Wenger-Trayner, B. (n.d.) Introduction to communities of practice. Retrieved from http://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

Your post is so transparent, Annie. By exposing your ideas of improvement, you make the rest of us feel comfortable to express our concerns and challenges. In discussing this with you during our Google Hangout, it made to start to think about sharing successes and challenges in my own school environment and really helped me to think about how this practice can be improved among my colleagues. Thank you for that. P.S. – Your infographics are better and better every week, hats off!

You made a small and significant point about the role of Twitter as a learning community. It would be interesting to research that topic further, but I’ find it to be crucial in connecting with others across distance and time and without a huge commitment. That is, you can make connections with experts who might not be willing to respond to a long email, but will engage in a number to Twitter mentions. I’ve taught on this very topic about how we can connect with others as a way of practicing scholarly community 2.o (https://wiki.spu.edu/display/LibTech/Scholarly+Communication+2.0). Thanks for your thorough post. Your excitement and depth of research are very evident.

Great job exploring the value of informal collaboration with colleagues. Finding the right person or group to collaborate with is also valuable. Your infographic design for supporting teachers who are exploring new technology is a great visual. This feedback loop model not only supports teachers implementing technology but also connects with student learning. Thanks for sharing!