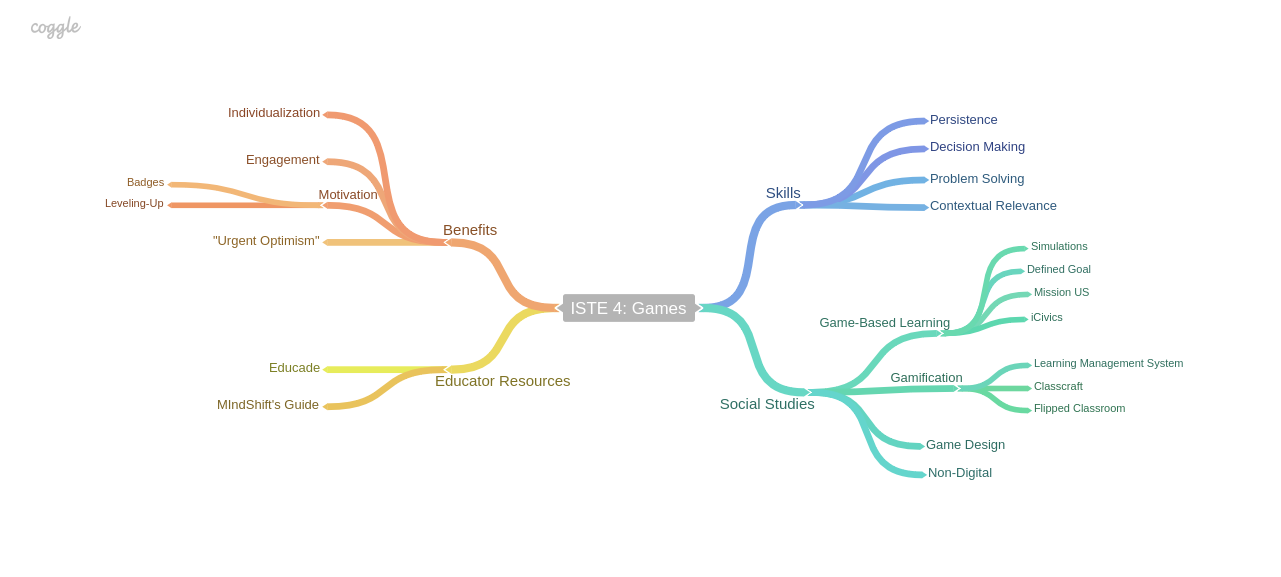

I am continuing my ongoing look at ISTE Student Standards with my graduate program in Digital Educational Leadership at Seattle Pacific University, and I encourage you to visit my previous posts addressing ISTE 1, ISTE 2, and ISTE 3. This week, my focus is on ISTE Student Standard 4 which addresses using critical thinking skills to problem solve and make informed decisions. These skills are necessary for any content area or age level, and can be learned through game-based learning (Sardone & Devlin-Scherer, 2010). Using games in education has become increasingly popular in recent years, as games reward small successes, while engaging and motivating participants. Games also produce less of a stigma around failure, since gamers simply persist until they beat a level.

The Power of Games in Education: What the Research Says

This investigation led me to bold statements claiming gaming is the future, as it has the ability to save failing educational systems…and even the world. Believing that humans are better at games than they are at real life, McGonigal (2010) claimed that gaming can make the world a better place. Gamer motivation is often tied to personal meaning, inspiring collaboration and cooperation (McGonigal, 2010). In games, individuals stick with a problem for as long as it takes to achieve success, propelled by urgent optimism, otherwise known as the desire to solve a problem immediately if one believes success is possible (McGonigal, 2010). These facts combined suggest that if gamer power is harnessed, real world issues could be solved (McGonigal, 2010). McGonigal’s (2010) latest project, a collaboration with The World Bank called Evoke, is designed to empower players to develop innovative solutions to dire social problems.

While the suggestion that gaming can save the state of education sounds improbable, “neuroscientists are discovering more and more about the ways in which humans react to such interactive design elements. They say such elements can cause feel-good chemical reaction[s], alter human responses to stimuli -increasing reaction times, for instance – and in certain situations can improve learning, participation, and motivation” (Anderson & Rainie, 2012, 2nd para.). A shift away from standard educational models, which rely heavily on direct instruction, would mean that “students have the responsibility for finding, analyzing, evaluating, and sharing knowledge under the direction of a skilled subject expert” (Bates, n.d. p.68).

Haskell’s (2014) Prezi took this idea one step further by highlighting the paradigm shift away from a grade book based systems towards a quest-based one. Quest based learning allows and rewards failure, promotes progress, and gives students individualized paths.

Following my initial research, I was left wondering…Should I drastically restructure my entire classroom model? What would gamification even look like in my classroom? I started by investigating a resource shared with me by @JaniessSallee called Classcraft, which is an online tool structuring gaming elements around existing curriculum. Content is taught and studied as part of the ongoing game, and rewards and leveling-up occurs as a result of mastery. Classcraft’s model bears similarities to a learning management system and a flipped classroom. Dominguez (2012) noted that gamification may result in improved student motivation and performance, but it does require a large amount of effort by the educator. A tool such as Classcraft would certainly requires this large amount of effort by the educator. At this stage, I wondered if there was another way to incorporate games into my classroom.

In “Gamification in the classroom: the right or wrong way to motivate students,” Walker (2014) shared that educators shouldn’t be swept away by the appeal of games that require uprooting the entire school model. If education must be masked in the form of a game, it can suggest to students that the learning itself isn’t meaningful (Walker, 2014). Rather, the focus should be on creating game-like situations for students to focus on inquiry method and project-based learning (Walker, 2014). As such, it is best to blend the current structure of instruction with new tools and techniques instead of uprooting everything already in place (Goli, 2013). This led me to focus my search on only one content area and see what I could find.

How can problem solving and decision making skills be taught using games in social studies content areas?

Understanding the difference between gamification and game-based learning is crucial. The implementation of Classcraft, for example, is gamification, or applying game mechanics to engage and motivate students to understand curriculum. Alternatively, game-based learning is a type of game play with more finite goals, and I decided that game-based learning was where I should focus.

Game-Based Learning Resources for Social Studies

A comprehensive but albeit overwhelming source for educational game options is MindShift’s Guide to Digital Games + Learning. This extensive and free document highlights one important takeaway -understanding available gaming resources is complicated. Distinct categories for educational games aren’t fully defined given the nature of the emerging market. However, I discovered three specific resources to share below: iCivics and Mission-US, two social studies game-based learning tools and EduCade, a website offering lessons paired with vetted games.

Mission US

Mission US is a free simulation game that allows students to go on four separate missions spanning over two hundred years of American history. Students can register without an email address or play without registering at all. Registering is preferred, as it allows students to keep track of their scores and compete. A narrative thread runs through the simulation as students are given an identity to complete the mission. Trailers and prologues set the stage for the journey, and essential questions and primary documents are embedded into the narrative. At many stages students are asked to make decisions and problem solve, and important vocabulary is taught and saved for students to refer to later, and educator guides available to align curriculum. If time isn’t available for students to play the entire simulation, Think Fast! About the Past, a fast-paced quiz game highlighting key questions, is a great alternative.

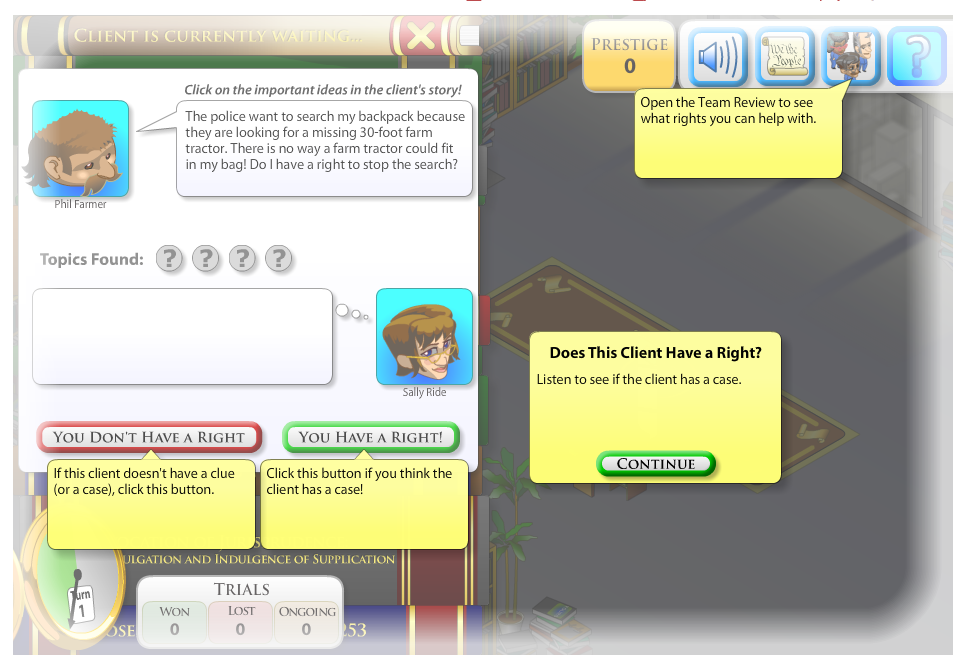

iCivics

iCivics is another free resource founded by Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. As the name suggests, its aim is to teach students how to make decisions about civic issues. Students have the opportunity to hear arguments in a Supreme Court cases, meet with clients in a law firm, run town hall meetings to address a State of the Union Address, and select Constitutional Amendments to support a court case. While the simulations are well guided, the responsibility is truly on the student to read and understand the issue to excel. You can play without signing up, but registering gives access to competition and leaderboards. Registering requires a student email address, but also allows teachers to create classes and assign games. Educators have access to aligned curriculum, and students’ points can be turned into community points to be donated to real charitable causes.

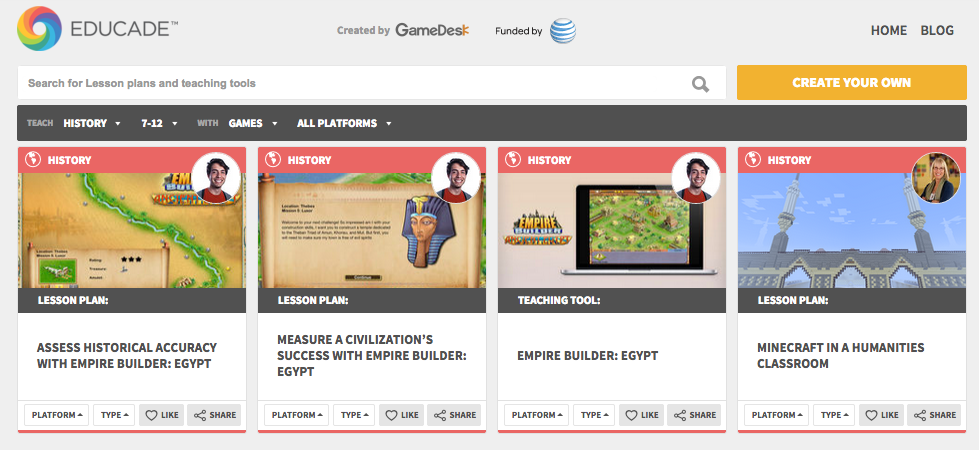

Educade

Educade is a repository of resources for play, making and discovery. Resources can be sorted by subject, grade range, tool type, and platform. Once you select a resource, you can see reviews in categories such as price, ease of use, tech requirements, and common core standard. An overview description and video are also included. Most notably, free lesson plans are provided that align with the use of the tool. Technology does not have to be a piece of fostering these skills, as Educade also highlights resources and games that are non-digital.

I would love to know what you think about this topic. How do you see yourself using games in your classroom? Share with me here in the comments section or Tweet me @AnnieTremonte. I am so intrigued by this topic that I think my next step is to read Reality is Broken by Jane McGonigal.

Resources

Research

Anderson J., & Rainie L. (2012). The future of gamification. Retrieved

from http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/05/18/the-future-of-gamification/

Bates, A. W. (n.d.). Theories of learning in a digital age. In Teaching in a digital age (3).

Retrieved from http://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/part/624-2/

Domínguez, A., Saenz-de-Navarrete, J., de-Marcos, L., Fernández-Sanz, L., Pagés, C., &

Martínez-Herráiz, J. (2013). Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Computers &

Education, 63380-392.

Goli, S. (2013). Can gamification save our broken education system? Forbes. Retrieved from

http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2013/02/21/can-gamificatio-save-our-broken-education-system/

Haskell, C. (2014, April 14) Blow up the grade book! [Prezi Presentation]. Retrieved from

https://prezi.com/-heueu0wnmk8/blow-up-the-grade-book/

McGonigal, J. (2010, February 10). Jane McGonigal: Gaming can make a better world. [Video

File] Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_gaming_can_make_a_better_world?language=en#t-4544

Sardone, N. B., & Devlin-Scherer, R. (2010). Teacher candidate responses to digital games:

21st-century skills development. Journal Of Research On Technology In Education, 42(4), 409-425.

Shapiro, J., Tekinbas, K., Schwartz, K., Darvasi, P. (n.d.) MindShift guide to digital games and

learning. Retreived from http://www.kqed.org/assets/pdf/news/MindShift-GuidetoDigitalGamesandLearning.pdf

Walker, T. (2014). Gamification in the classroom: the right or wrong way to motivate students.

NEA Today. Retrieved from http://neatoday.org/2014/06/23/gamification-in-the-classroom-the-right-or-wrong-way-to-motivate-students/

You’ve done an outstanding job of exploring gamification and game-based learning to help you solve your driving question. You’ve also successfully narrowed your focus, summarized your learning, and incorporated excellent artifacts to support your narrative. I hope you’ll continue to explore and even incorporate elements of gamification and game-based learning into your classroom. Enjoy Reality is Broken! I shall check out Educade.

This is really inspiring, Annie! I never realized how strongly people felt on both sides of game-based learning and gamification. Your use of embedded videos and images really pulled everything together and your conclusion with next steps for both us (the readers) and yourself is great. Nice job, Annie!

Thank you for your very thorough and interesting blog post, Annie. You provide a great overview about the differences between game with gamification and game based learning. I think what is nice about your post, in particular, is that pretty much anyone could come to your post and walk away with a good understanding of game based learning and gamification. Additionally, you provide helpful resources for someone to implement in their course right away. Thanks, Annie and I look forward to hearing more about how your implementation of game based learning activities goes in your class.