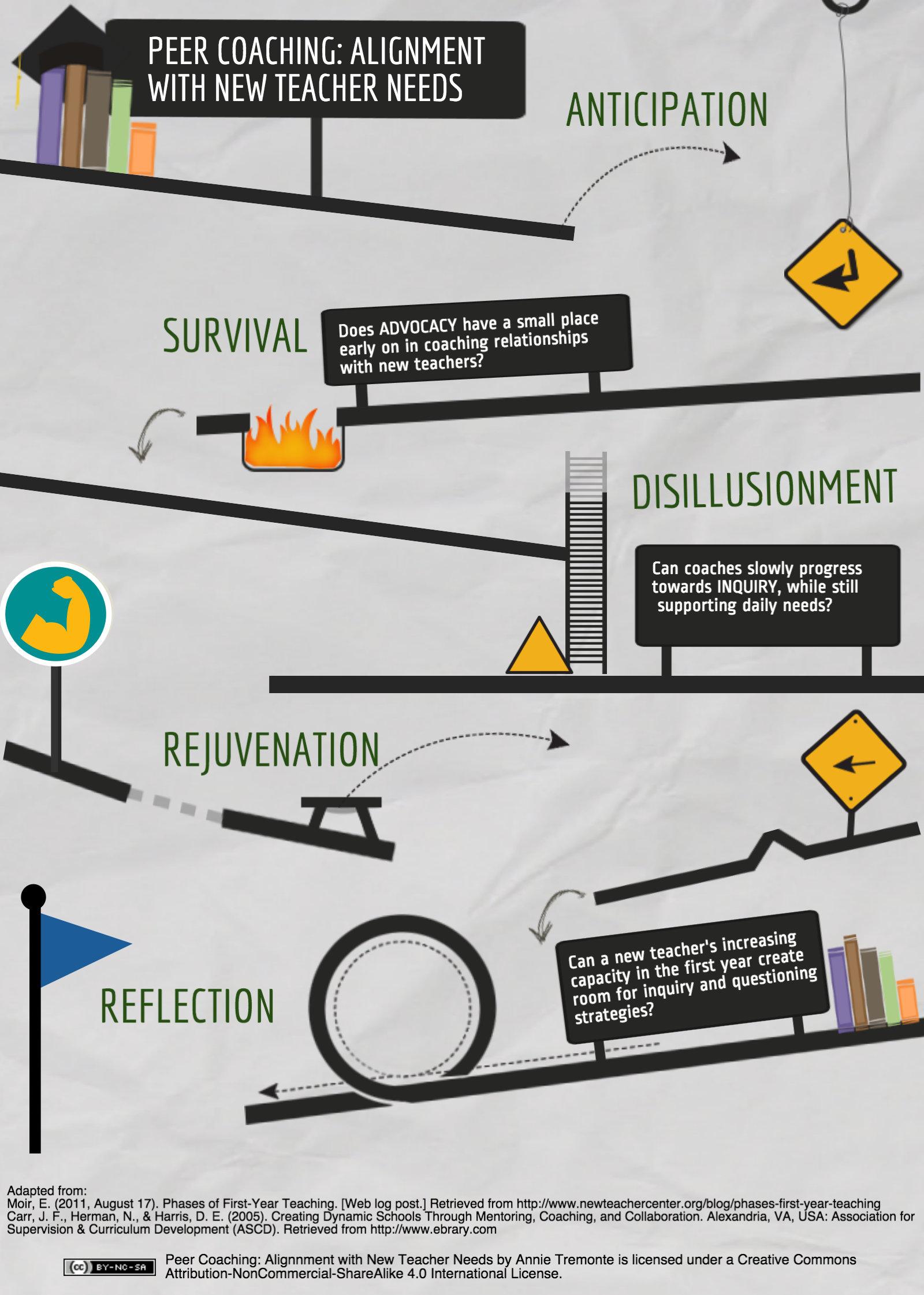

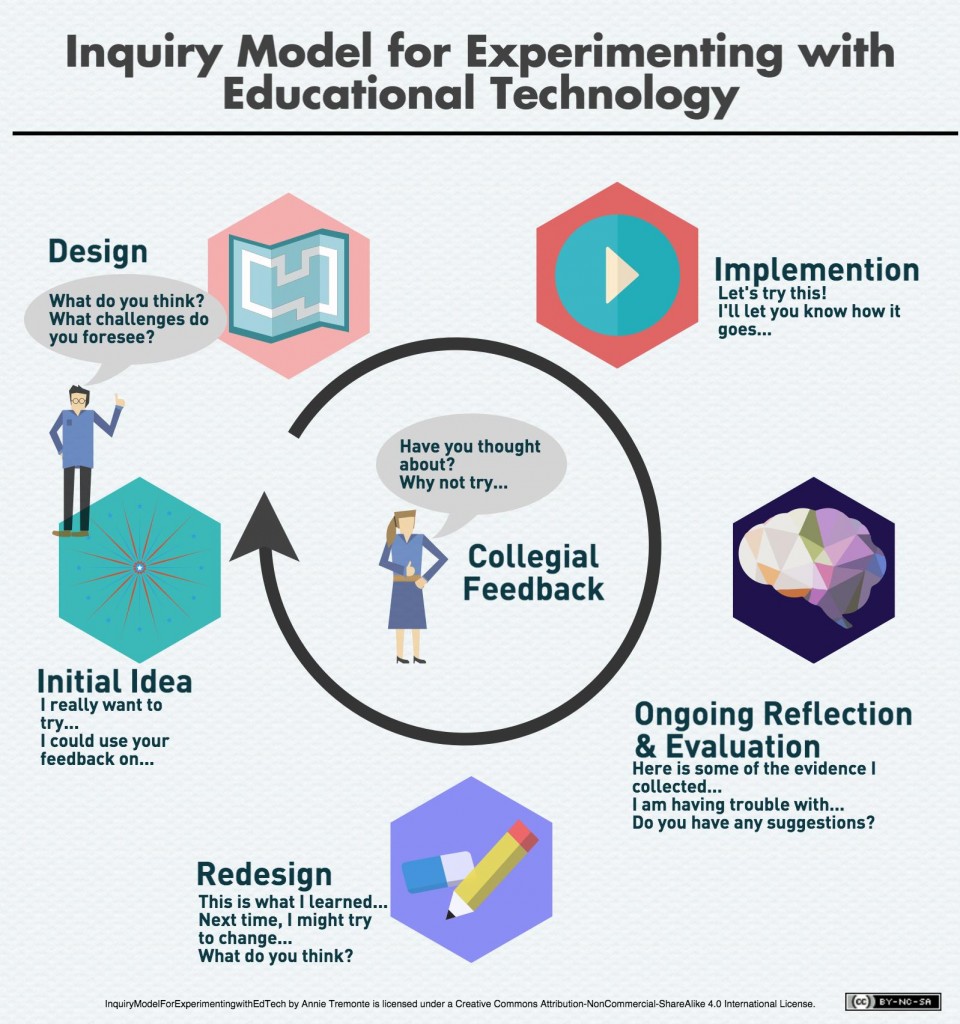

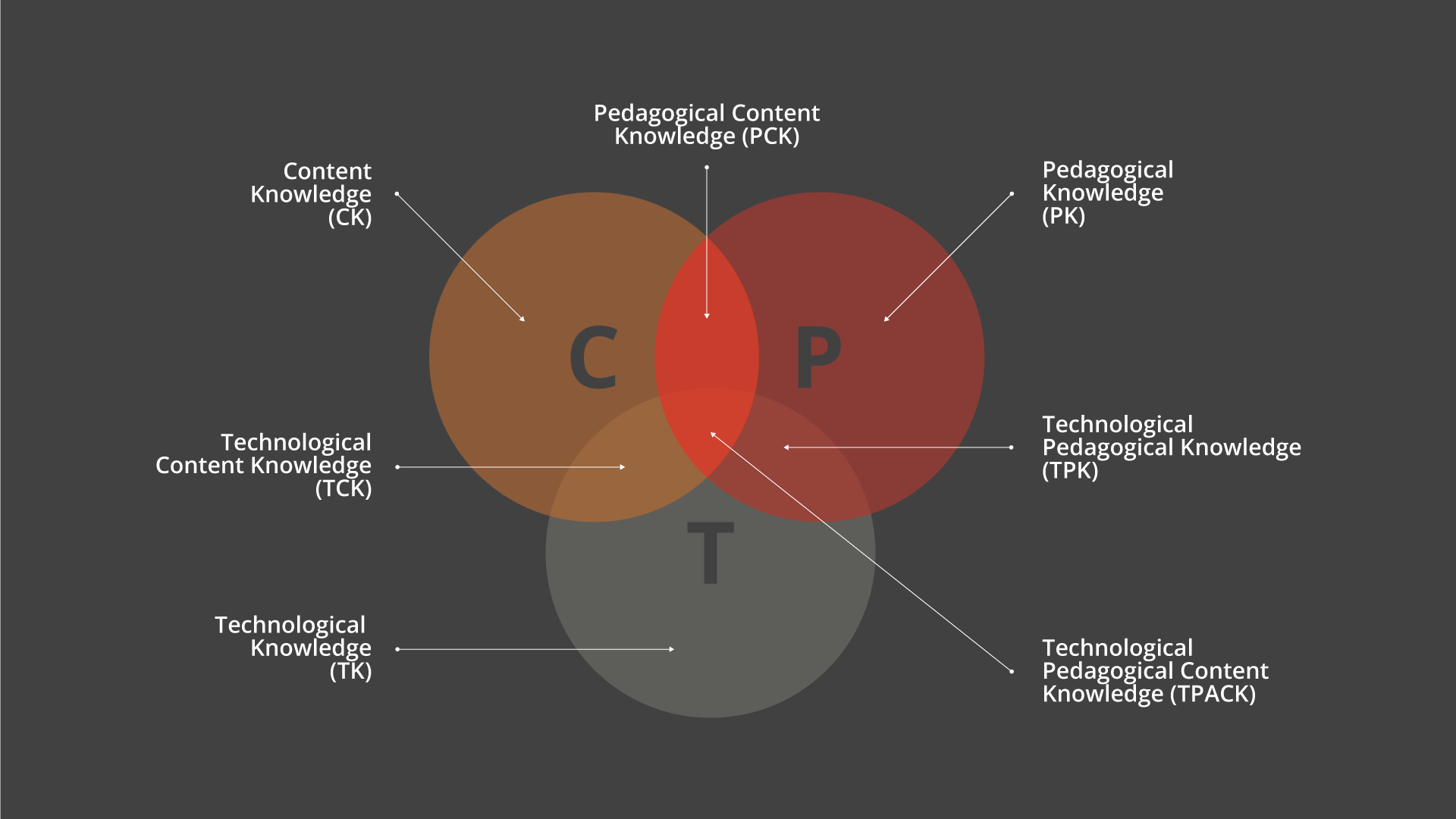

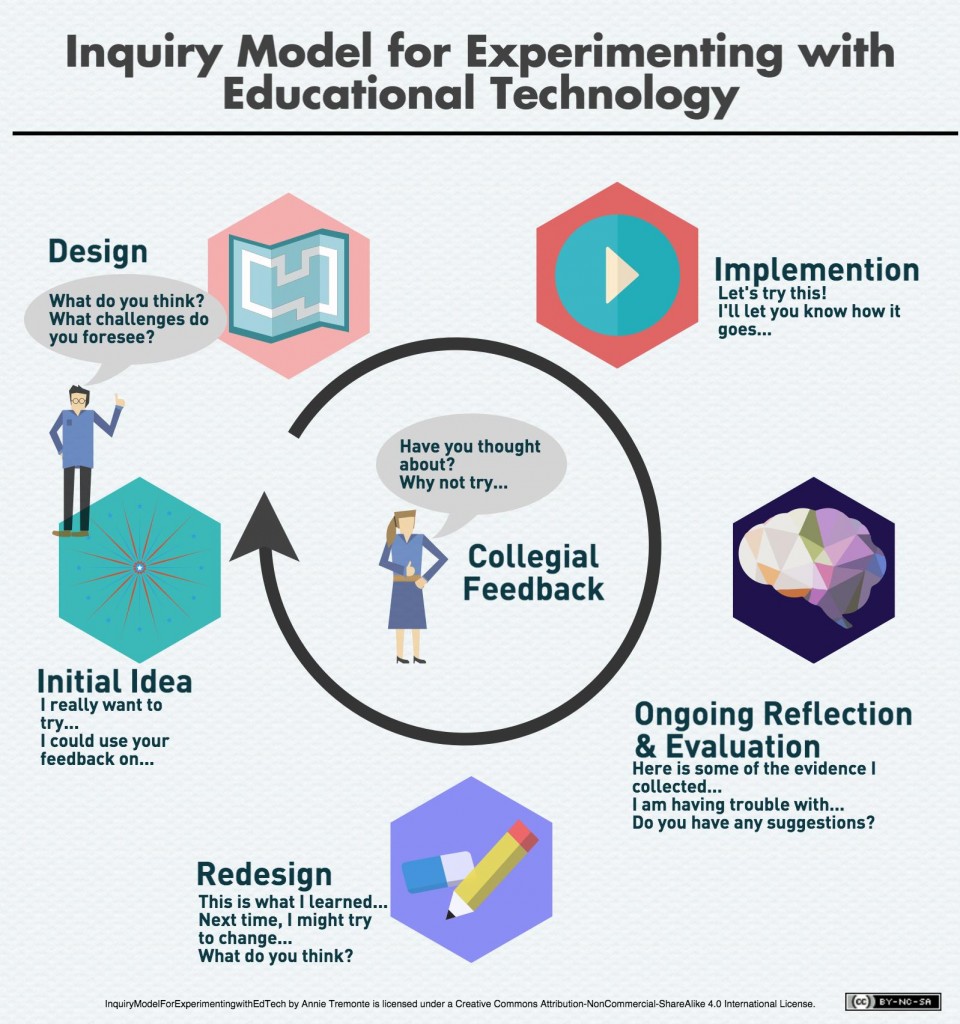

In my last post, I examined how perceptions shape our beliefs. I also commented on how this has impacted the implementation of educational technology. As I think about how perception has prevented those in my own school community to resist a BYOD practice, I have been thinking about my past exploration of unconference models. Many attest to the fact that teachers learn best from one another. Knowing this, I have been wondering how I can broaden the practice of learning collaboratively to my entire school. In a past post, I investigated the unconference model, a more informal collaborative form of professional development. I shared what I’d learned from attending two EdCamps, noting how collegiality and collaboration impacts instructional practices. I also commented on the impact of autonomy and personalization on our development as educators. I have also previously shared my informal collaboration with a colleague last year, exploring technology enabled learning by holding conversations on practices that worked and didn’t. The inquiry model infographic I designed below showcases our method.

I merged this inquiry method with my reflections on the unconference model to come up with the video below, a vision of how this model might transfer into monthly sessions at my school.

Some questions posed by @RMoeJoe and @EllenJDorr left me thinking further about how to accomplish an unconference model as part of a BYOD action plan.

- How have unconference models worked in the past?

- Where are evident spaces for it in my K-12 environment?

- What do I need to invent on campus to help it foster?

- What supports can I offer to help my colleagues and system to continue growing?

Although this approach to professional development saw its start in the tech industry, its influence is growing in education. The significance of the unconference model is that, as the name suggests, it dispels some of the previous notions of how professional development should work (Howard, 2010). For example, unconferences are propelled by the attendees, not the facilitators, bringing democracy to professional development (Howard, 2010). Normally, professional development asks attendees to choose from pre-determined presentations. With the unconference model, attendees propose the topics for workshopping and discussion together, not for presentation from one person at the front. Howard (2010) shared that an online space be created for participants to suggest ideas of interest and exploration. I did broach a similar idea in my video above, suggesting users pitch ideas on a forum like Padlet for popular vote. AnswerGarden is another tool that can be great for this, and I’ve seen it used spontaneously at EdCamps as late as the very start of the session. And, if interest isn’t high enough, the topic isn’t discussed (Howard, 2010). With the motto that “user-generated is the guiding principle,” the focus is on teachers’ needs, not the directives of administration (Howard, 2010, para. 4). Fostering personalization and leadership for all teachers involved is an extremely empowering practice which might influence buy-in.

Attendance is usually smaller than that of a real conference, which does make it an easily transferable model for recurrence in a K-12 school environment. It is loose, informal, but not without norms and procedures. I thought a lot about the word informal during the crafting of my last posts on this topic. I felt that the work I did with my colleague last year was altogether informal, but I realized that we did have norms for our conversations which is how I came to link our practice to the inquiry model above.

It Belongs to Everyone

The sessions don’t belong to the facilitator; they belong to everyone in attendance (Watrall, 2010). As a result, decisions, conversations and leadership are driven by everyone in the room (Watrall, 2010). Budd et al. (2015) called this “participant-centric thinking” and noted that this style is what separates it from traditional models (2015, p. 3). The empowerment of participants, who are aware of their important contribution to the process, leads to more investment and often better results (Budd et al., 2015). This is also perhaps the key to fostering buy-in and sustainability. Just like the teacher is shifting from the sage on the stage to the guide on the side, so too is the PD facilitator. My colleague @Ingersoll_Ryan said in his feedback that my focus on valuing the input of teachers is key. Perhaps part of valuing teachers to participate is to seek out and encourage colleagues in my building with unique expertise and perspectives to participate (Budd et al., 2105). I hadn’t thought about reaching out beyond those who show up. I should reach out to colleagues who have reservations about implementing technology BYOD. I should reach out to those I know are doing interesting tech-enabled learning in their classrooms. I should reach out and invite administrators and our IT support personnel to take part in conversations. This will send the message that all teachers are valued in this conversation, not just those who are already interested.

I wholeheartedly agree with Budd et. al (2015) that some of the most influential conversations to instructional development and relationship building often take place in the space between typical professional development, as well as during before and after school visits with colleagues. Budd et. al advocated that the unconference model should “prioritize conversation over presentation” (2015, p. 2) I wonder if it might be useful to survey my colleagues on their perception of how they best learn professionally. Might they also agree that we often learn better from each other than we do from large scale presentations? Involving my colleagues in this initial question might lead to more interest and buy-in.

The Details: Environment, Anxiety and Communication

Breaking down the formality of a classroom or presentation hall should also be considered. Just like we are shifting our own classrooms to be more student-centered and collaborative, so too should this model. Arranging desks to form circles or clusters for breakout sessions, or even getting out of the classroom in pursuit of more comfortable seating shouldn’t be disregarded as helpful (Watrall, 2010) .

I have been asked multiple times by my cohort and professors how I will lead my colleagues to be active participants in the discussion of BYOD and/or the pedagogical approaches to technology. Asking teachers to engage in regular conversations is a good place to start, although this might incite anxiety. In my first EdCamp, I was very anxious about being asked to lead or speak. In my second, I spoke but still had anxiety about it. Fears such as public speaking or engaging in debate can be concerns in the transition from a passive listener to an active participant (Budd et al., 2015). However, creating an environment that values those in it and carves out a place for all those involved, by giving credence to contributions can build confidence (Budd et al., 2015).

Part of valuing participants is creating a public online space to contribute ideas. Whether through a living online document or via ongoing online conversations, this creates an additional opportunity to be heard by one’s peers, to have a clear influence, and to gain confidence (Budd et al, 2015). It also provides the opportunity for the work accomplished to be lasting. I mentioned the use of Padlet and AnswerGarden, but Twitter is often used to stream conversations occurring during and after. Google Docs is another tool often used to document collaborative activity in real time.

@EllenJDorr also asked how I can prove my theory of action and offer entry points so anyone could join my movement. This is a tough question. The need to accrue clock hours towards re-certification makes professional development a paperwork issue. My school has strict policies for how to run PD and while I could choose not to worry about getting paid as a facilitator, negating clock hours for participants would certainly prevent buy-in. Accountability is required from sign-up to attendance so registration unfortunately stays rigid. As a result, adding additional participants throughout the year might be a difficult to approve. I’ll have to this on this!

Conclusion

Budd et al. stated that “The idea that no individual person has all the answers promotes a spirit of generosity, interaction, and respect amongst all participants. Every voice is valued” (2015, p. 3). This seems to say it all. I think I should even post this for my students in the classroom.

Resources

Watrall, E. (2010). Notes on organizing an unconference. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/notes-on-organizing-an-unconference/24028

Howard, J. (2010). The ‘unconference’: technology loosen up the academic meeting. The Chronicle of HIgher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/The-Unconference-Technology/65651/.

Budd, A., Dinkel, H., Corpas, M., Fuller, J. C., Rubinat, L., Devos, D. P., & … Wood, N. T. (2015, January). Ten simple rules for organizing an unconference. PLoS Computational Biology. pp. 1-8.